“Honest Labor Bears A Lovely Face” *

Yamileth, tortilla maker and restaurant owner, Cerro Pittier, Costa Rica, 2016

In this blog for the past year you have seen mostly photographs of my connections to the natural world. Not today. I also like photographing people, and for a change, I’m publishing some photographs of strangers I’ve met over the last forty-six years. My next post will show children and young people.

In Boston and San Francisco where I lived before moving to Costa Rica in 1988, I made a point of regularly visiting private galleries and museums exhibiting fine photography, a strong interest of mine ever since a friend gave me an SLR camera when I was twenty-two years old. I was attracted to the work of several well known street photographers, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Helen Levitt, and Nicolas Nixon. Their work was in black and white. Then came Joel Meyerowitz and William Eggleston who were the first to receive critical recognition for working in color. Inspired, I followed the market for fine photography, even acquired a few prints for myself. And on weekends or when visiting other cities I went out on the street with my old Minolta loaded with color film.

One early German portrait and documentary photographer, August Sander (1876-1964), made a lasting impression. He specialized in portraits of German people from all walks of life, whether in high society, government, or working at their trades. His monumental catalog of over 600 portraits included the baker, bricklayer, soldier, miner, architect, shoemaker, cleaning lady, blind veteran, bourgeois mother, parliamentarian, organ grinder, and so many more. Somehow, though the faces are staring directly into Sander’s lens, many do not appear formally posed. Most are unsmiling. Yet they look natural, authentic, and simply unconcerned about the presence of the photographer. His photographs have stood the test of time.

Shoeshine Man, New York, New York, 1972 (digitized from aged slide)

Sander said “We can tell from appearance the work someone does or does not do; we can read in his face whether he is happy or troubled.” He also said “I never made a person look bad. They do that themselves.” In the 1930s the Nazis banned Sander’s portraits because many were simple folk who did not conform to their Aryan ideal. He also had started making portraits titled “Persecuted Jew” or “Political Prisoner”. After he was threatened, he turned instead to natural landscapes and architectural work. However, it is his early work documenting the people of his region that made him one of the best portraitists of the 20th century.

Have I been influenced by some of the greats mentioned above? I have few illusions, but from sheer acquaintance, repeatedly, with their work, marks of style were etched in my memory, and they inspire me to look closely at people, especially when they are working. Few photographers could achieve the dedication of Sander, who spent his entire adult life creating portraits of “Man of the Twentieth Century”, but I still try from time to time to pay respect to interesting strangers I encounter along the road of my own life.

Tree cutter, San Vito, Costa Rica, 2008

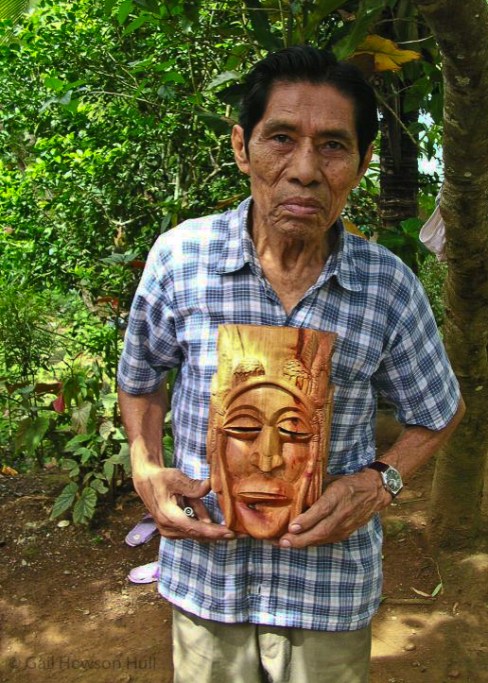

Ismael Gonzalez, master mask carver, Boruca, Costa Rica, 1999

Ceramacist, Chorotega-tradition, Santa Cruz, Costa Rica, 1998

“Tapichero”, sugar cane processor, Perez Zeladon, Costa Rica, 2008

Boruca calabeza gourd carver, Rey Curre, Costa Rica, 1996 (digitized from aged slide)

Field worker and farm caretaker, San Vito, Costa Rica, 2008. Minor Rodriguez worked for me full time for six years.

Campesino farmer at dog and cat neuter and spay clinic, San Vito, Costa Rica, 2014

Honey and fruit juice seller, Puerto Viejo, Costa Rica, 2006

Stage doorman, New York, New York, 1972 (digitized from aged slide)

Lifeguards, Crane’s Beach, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1970 (digitized from aged slide)

*Thomas Dekker (1572-1632) from his play Patient Grissel (1603), Act I, sc. 1.

To email me about this post, please click here.

- July 26, 2016

- people

- Comments closed

Winsome Owls

Crested Owl, Lophostrix cristata Stricklandi, dark morph

A wise old owl lived in an oak

The more he saw the less he spoke

The less he spoke the more he heard

Why can’t we all be like

That wise old bird.

Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, 2nd ed. 1997, #394

There is no doubt that people are drawn to owls. They are quiet, except when calling out at night while looking for a mate, and their nocturnal habits of silent flight and binocular vision are intriguing and mysterious to us. They have roundish faces (like our own) and large penetrating eyes, suggesting a seriousness to which we ascribe wisdom. Farmers value Barn Owls because they protect grains from rodents. While most birds fly off nervously at the approach of Homo sapiens, owls seem indifferent to us, sometimes sleeping through observers’ excited whispers about spotting such an uncommon creature. There is something almost talismanic about these birds of prey that inspire many of us to collect owl-themed art, t-shirts, crafts, or knick-knacks. And this week I learned that a young friend is heading next month to Warren Wilson College in North Carolina, a small liberal arts college with a strong curriculum in environmental and conservation sciences. The college’s mascot? The owl!

Crested Owl, Lophostrix cristata Stricklandi, photographed at Finca Pino Colina in 2015

On June 24th an 11-year old boy in the “Earth Caretakers” youth group (“Guardianes de la Tierra”), from the nearby town of Sabalito, spotted a Crested Owl (Lophostrix cristata Stricklandi) in a tall bamboo clump near our Laguna Zoncho at Finca Cántaros. In Spanish it is known as Bújo corniblanco or Búho penachudo. As word has gotten around, there has been a steady stream of birders eager to see Costa Rica’s second largest, strictly nocturnal owl. It is rare in some areas and fairly common in other parts of the country, but it is certainly the first time we have seen it in our 22 years at Finca Cantaros.

The Crested Owl’s habitat extends from sea-level up to 1900 m with one sighting in a Honduran cloud forest at 1950 m. Three subspecies of Lophostrix cristata are recognized, and our current resident is the dark morph (variant form of a species of organism*) of the subspecies Stricklandi, first described in the year 1800 and now found from S. Mexico to W. Panama. The “dark morph”, as in this case, has a blackish face and forehead, dark rufous around eyes, eyes usually yellow-orange, as opposed to the pale morph, with facial disc tawny to chestnut, underparts plain buffy-brown to pale grey-brown, iris dark brown. (The other two subspecies are in South America.) The Crested Owl weighs between 400-620 grams (14 oz to 1 lb 5 oz) and measures 36-43 cm (14 to 16.9 inches).

When “our” owl disappeared for the day July 12, I went underneath its perch of the last 18 days to search for signs of what it might be eating. Strangely enough, there were no visible droppings whatsoever. My interpretation of this lack of evidence of digestive processing is that the owl only poops when it flies. The reference literature says that the Crested Owl eats mostly beetles, roaches, caterpillars and other orthopterans, but may also eat small vertebrates. Happily, on July 13 the owl was back on the same branch, with its excellent view of the lake edge, where frogs, lizards, and snakes surely move about at night. I hope it will continue to find prey so that we, and visitors to the reserve, can appreciate it for many weeks to come.

Burrowing Owl, Athene cunicularia, photographed in the Pantanal region of Brazil, 2013. This diurnal species uses the holes of small mammals in which to create a nest made of dried cattle dung, automatically attracting insects to feed chicks. During the day they rest on cattle fence posts.

References:

Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive.

A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. F. Gary Stiles and Alexander F. Skutch, Comstock Publishing Associates, A Division of Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY., p. 192.

*Dictionary of Science, Robert K. Barnhart, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, MA, 1986, p. 416.

To email me about this post, please click here.

- July 14, 2016

- fauna

- Comments closed

Finding at Las Cruces the “Impartial Calm of Nature”

View of Fila Cruces from the Canopy Tower, 6:30 AM, 26/06/16

Lately I have become more zealous in my desire to photograph birds. When I lived and worked within the grounds of the Wilson Botanical Garden (WBG) as associate director from 1988 to 1999, I recall marveling at the photographs of many of the over 400 resident and migrant bird species taken by professional photographers. My work there–in charge of development and visitor administration– represented a dramatic change of career and lifestyle for me, and I used my camera as much as possible to record people at work and on vacation—scientists, students and bird and plant aficionados, but I never thought I could be a bird photographer myself. It takes time and a patience that I didn’t then have! But now that I’m “retired”, I’ve been able to find that time and patience to attempt the challenge, and this blog, I hope, is a testament to that.

Scale-crested Pygmy-Tyrant

Hoping to see birds that aren’t found here at Finca Cantaros, I decided last weekend to visit my old stomping ground, the Las Cruces Biological Station, which incorporates WBG. Leaving home early, I arrived at Las Cruces before 6:00 a.m. on both days. I saw almost no one as I made my way to the steel “canopy tower” built not far inside the forest.

On my way I saw an agouti female and juvenile foraging, and from the 4-story tower platform I was entranced by a baby squirrel, birds, bees and butterflies, trees flowering and fruiting, fog floating over the forest canopy and into topographical hollows.

Green Honeycreeper, male

Clouds rolling over the nearby ridge provide the humidity needed by thousands of arboreal orchids, bromeliads, ferns and other epiphytes clinging to forest trees. It was damp and cool, but I was warmed by a state of heightened energy and connection to this place I know so well. Within the Wilson Botanical Garden (WBG) that I passed through to get to the forest tower, palms and trees that were planted as seedlings before my eyes in the early 1990s are now stalwart specimens rising high overhead. I began to think back to my early days here and what drew me to this wonderful corner of Costa Rica.

Though palms are everywhere in WBG, this view is on a trail dedicated to diverse palm species.

There is a timeline to our lives, but we sometimes can’t recognize the relative importance of events as they are happening. We may have minimal perspective, until years later. As a child, I was an intrepid explorer in the wilds of my environment. Even if it was exurbia, there were woods, ponds and brooks that attracted me. As an adult, I didn’t allow much time for the natural world and focused instead on work and the cultural life of the cities where I lived. I know my friends and family were anxious when I left the San Francisco business world in 1988 to take a job with OTS and to marry someone from another culture, the botanist-director of Las Cruces, Luis Diego Gómez. They needn’t have worried, though my marriage ultimately failed. I was reconnecting my life to the natural world— the rich vibrancy of the tropics.

To Luis Diego, alas, deceased in 2009, I will always be grateful for the botanical knowledge, and much more, that he shared with me. He and the OTS staff at Las Cruces welcomed me and made me feel that Coto Brus was my home from the very first day.

Maidenhair fern, or “culantrillo” in Spanish, Adiantum macrophyllum.

on Tree Fern Hill at WBG. New leaves of this species are bright pink instead of the usual reddish color of other ferns in the genus. (Thanks to Robbin Moran, Ph.D., NY Botanical Garden for ID.)

Many aspects of life at Las Cruces appealed to me, but best of all was being able to work with—and learn from—tropical scientists. I also felt part of a historical custodianship in which all players along the way have had a positive impact upon the land; I believe Luis felt this strongly, too. When Luis arrived in 1986, an impressive tropical garden with an attractive infrastructure of trails, stone walls and steps was already in place. But Robert Wilson, a Florida horticulturist, and his wife Catherine, who had purchased the property in 1962, were aging, and needed fresh botanical ideas and a steely-minded planner and implementer. They found that person in a fern and fungi specialist, Luis Diego.

Stone steps within Wilson Garden covered with flowers from manzana de agua tree, Syzygium malaccense, or Malay Apple.

Fortunately, in laying out the gardens Wilson had consulted with one of the most renowned landscape architects in the world—Brazil’s Roberto Burle Marx. However, there remained much creative gardening for the new director to do, and together he and I faced a desperate need to build a laboratory and civilized accommodations for long-term resident scientists, short-term students, artists, birders, plant enthusiasts and volunteers. Visible improvements came slowly, but very surely. Foundations and generous individuals stepped up to support OTS’ mission, including providing funds to double the size of the forest reserve through two land acquisitions secured in 1993 and 1998. Las Cruces was always, and remains, a cosmopolitan high-energy center that not only changes peoples’ lives, but protects a growing biodiversity with each new land acquisition!

My photo from the Dec. 1991 Amigos Newsletter of botanist Robert W. Lichtwardt, Ph.D, U. of Kansas, collecting aquatic insects from bromeliads with a turkey baster. He studied the systematics and ecology of Trichomycetes–gut fungi of insects and other arthropods. As editor of the Amigos Newsletter, I asked scientists to write articles–no one ever turned me down!

Thoughts like these passed through my mind as I was standing at the top of the canopy tower, and were almost a distraction from my mission to photograph birds. I did get some, but upon getting home, the trip down memory lane inspired me to go through some old photos and reflect on how things have continued to improve at my former home and life at Las Cruces.

Reading the farewell message and assessment of progress by Las Cruces director and forest ecologist, Zak Zahawi, in the latest Amigos Newsletter, and from the vantage point of 17 years since my own departure from LC, I can only marvel at how much has been accomplished since Robert and Catherine Wilson arrived in 1962 and invested all their aspirations into that forlorn cattle pasture which became the cultivated garden.

Buttress roots and diverse plants suggests the wild nature of the Wilson Garden.

If Zak is having mixed feelings about leaving Las Cruces after ten years of hard work, I can certainly understand. Though catering to the public, scientists and students day-in and day-out is difficult, to live in such a tropical garden, and share it with others, is a very special privilege.

I call upon some stanzas from a Rainer Maria Rilke poem I discovered recently, to express my sense that, though I was impulsive about leaving my life in San Francisco in 1988, I knew instinctively what I was doing was right.

Yours truly, Gail Hull, in 1989 with the tallest endemic Cycad (over 10 ft to top of crown) Zamia fairchildiana plant I ever found in the LC primary forest. This plant species became the focus of my own research as an amateur. Photo: L.D. Gómez

#54 from “Orchards”

In the animal eye I saw

a peaceable life enduring,

the impartial calm

of nature, imperturbable.

A beast knows what fear is

but keeps going nonetheless

and in its field of plenty

a certain presence grazes

with no taste for someplace else.

And additional stanzas in homage and with best wishes to Zak Zahawi:

Unidentified vine in the Las Cruces reserve.

The sublime is departure.

Instead of following, something

In us starts going its own way

And getting used to heavens.

Isn’t art’s extreme encounter

the tenderest farewell?

And music: that last glance

that we ourselves throw back at us!

[Rainer Maria Rilke, The Complete French Poems, translated by A. Poulin, Jr., Greywolf Press, 1986, pp. 167 and 193.] To read original French, see below:

Vergers #54

Baby squirrel seems to be eating and licking wood in the crux of a tree next to the Canopy Tower.

J’ai vu dans l’oeil animal

la vie paisible qui dure

le calme impartial

de l’imperturbable nature.

La bête connaît la peur;

mais aussitôt elle avance

et sur son champ d’abondance

broute une présence

qui n’a pas le goût d’ailleurs.

Portrait Intérieur #33

Le sublime est un départ.

Quelque chose de nous qui au lieu

de nous suivre, prend son écart

et s’habitue aux cieux.

La rencontre extrême de l’art

n’est-ce point l’adieu le plus doux?

Et la musique: ce dernier regard

que nous jetons nous-mêmes vers nous!

- July 2, 2016

- fauna, flora, landscape, people

- Comments closed

-

Recent Posts

- Movers & shakers and kleptoparasites September 5, 2021

- Birds That Cheered Me in 2020 January 2, 2021

- Solitude for Art and Birding September 25, 2020

- PHOTOGRAPHY BEARING WITNESS May 4, 2020

- DESERT BIRDS OF ARIZONA March 26, 2020

- BOSQUE DEL APACHE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE January 10, 2020

- Santa Fe Trails September 28, 2019

- A Hybrid Bird at Finca Cántaros January 17, 2019

- Birding at Caño Negro National Wildlife Refuge September 17, 2018

- Remembering the Bush Dogs June 8, 2018

Archives by month

Click the icon below to visit Finca Cantaros on Facebook:

Search Foto Diarist

Search Post Categories

-

Join 111 other subscribers

RSS Links

Blogs I Follow