What do beetles want?

Leaf-mining Tortoise Beetle in the Chrysomelidae family, Finca Cantaros

It may be only kids, scientists, artists and designers who see in beetles something to celebrate. Entomologists certainly appreciate beetles’ remarkable niche-finding evolutionary ability to adapt to most environments and climates on earth. We know beetles are successful because there are 400,000 species collected, many of which have yet to be officially described. Artists and designers likely see in some beetle species glorious color and symmetry (and stripes and polka dots), for in few other insects do we find such astonishing flamboyance. And kids just think most insects are pretty cool, especially beetles and butterflies.

Tortoise Beetle in the subfamily Cassidinae of the leaf beetles, or Chrysomelidae, Las Cruces Biological Station

I first learned about beetles, the order of Coleoptera, in elementary school discussions of the cotton boll weevil, such powerful pests that they changed economic conditions in the cotton-dependent southern United States. The boll weevil lays its eggs inside cotton bolls, and the larvae eat their way out. Weevils–Curculionidae–constitute the largest family of beetles; in fact, they are the largest group of living organisms, with 60,000 described species.

What do beetles want? Most want to live on or inside their food source. In my own nature reserve, Finca Cántaros, I see them embedded in rotten wood, chewing or sucking their way through heliconia petioles, flowers, palms, cacao pods, coffee beans, and leaves of countless plants and trees. Dung beetles…well, you know what they do. Beetles are more numerous within the high biodiversity of the tropics: there are simply more species of everything for insects to eat due to higher heat, more abundant rain and sunshine than in temperate zones.

Long-horned beetle (wood-boring), Amistad Biosphere Reserve, Pittier entrance

Beetles also want us! I learned that beetles from eleven different families feed on vertebrate carcasses and human cadavers. I’ve been leaning toward cremation for my post-mortem remains, but now I’m certain that is the way to go! As fond as I am of beetles, I must admit I don’t like contemplating being a food source for them; and the choice of cremation does seem to favor more responsible land use.

Weevil, Cholus cinctus in the Curculionidae family, a pest of ginger plants. Amistad Biosphere Reserve

While many beetles are pests, eating their way through the zinnias and roses in our flower gardens as well as forests of pine trees, groves of citrus, and many other trees and crops, other beetles have a positive role as major pollinators. The US Department of Agriculture site states that beetles are responsible for pollinating 88% of the 240,000 flowering plants globabally. (And I always thought bees deserve most of the credit!) Fossil records show that beetles were pollinating the earliest flowering plants on earth in the Mesozoic period–about 200 million years ago. Many current day plants, such as the Magnolia, a primitive angiosperm, have pollination relationships with beetles that have very ancient evolutionary beginnings.

And some beetles, such as Carabid ground and tiger beetles that live on the surface of the soil, are important consumers of destructive pests, like aphids, caterpillars, maggots, and slugs.

Anyone who enjoys readings in natural history has probably come across the musing by J. B. S. Haldane, a Scottish biologist and geneticist, while he was attending a meeting of the British Interplanetary Society in 1951. Reflecting on the fact that there are 400,000 species of beetles, as opposed to 8,000 species of mammals, he quipped, “The Creater, if He exists, has a special preference for beetles.”

As an artist and photographer myself, I have thrilled to rare discoveries in the wild of a flashy or bizarre beetle. To have the opportunity to photograph them is a gift. I have also admired artists, going all the way back to Albrect Dürer (a gifted German who lived from 1471-1528–see sidebar), who find inspiration in the “smaller majority” of life–the insects. Scientists never lose the urge to understand the world, and artists recognize in beetles some of our world’s highest creative achievements.

References:

Escarabajos de Costa Rica: Beetles, The Most Common Families and Subfamilies, 2002 by Angel Solis, 2nd ed., Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, Costa Rica

The Smaller Majority by Piotr Naskrecki, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; London England, 2005, p. 15.

- October 20, 2016

- fauna

- Comments closed

Blue-black Grosbeak parents are busy in August

Blue-black Grosbeak male carrying seeds to two growing nestlings.

When the winter rains of Costa Rica are upon us in August, I don’t expect to see avifauna tending their young or building new nests. However, that’s exactly what resident Blue-Black Grosbeaks are doing when rainfall measures between one-half to one inch of rain at least three days a week, and it rains most days of the month at this time of year. Nests built when torrential rains are common must be strategically constructed under protective leaves so the nests stay intact and the hatchlings stay dry.

In the first week of August my friend Alison Olivieri took me to observe activity around a nest at the forest edge behind the Wilson Botanical Garden, part of OTS’ Las Cruces Biological Reserve. We watched from a distance as the adults kept a wary eye on us, and both the female and male made visits to the nest in the half hour we watched. Seven days later I went back to observe from a hillside about 22 feet away, with better afternoon light on the vegetation the adults used as a safe staging area before approaching their nest.

Female Blue-black Grosbeak casts a glance at me before carrying food to the nest.

During the seventy-five minutes in early afternoon that I sat on the ground observing, the female visited the nest twice and the male visited once. Communication between the parents while they searched for food was with loud metallic “chinks”, typical of the species.*

Grosbeaks are seed-eaters and -crushers. Their diet is mostly vegetable, including grass and bamboo seeds, maize, and the dark blue fruits of Psychotria brachiata in the coffee family (Rubiaceae). Young are fed mostly mashed vegetable matter, but insects may occasionally be part of the menu.

Female carrying food looks around carefully to be sure it is safe to approach the nest.

What I have learned is that nest building among Blue-black Grosbeaks in Costa Rica occurs mostly in July-August, but earlier in some areas, including the wet Caribbean lowlands. Some pairs have two or three broods in a year. Both parents help with the building of the nest, which is an open cup made from fine twigs, coarse fibers and rootlets. The Handbook of the Birds of the World reports that nests are placed between 0.3 and 5 meters up in spiny palms, tree ferns, or similar small trees. Indeed, the Las Cruces nest I observed was only two feet (0.6m) from the ground and sure enough, was attached to bromeliads and epiphytes on an old tree fern.

Female Blue-black Grosbeak about to feed hatchlings.

The clutch usually has two eggs, as was the case with the Las Cruces nest. The female is alone responsible for incubation, and she is fed “to a variable degree” by the male. However, both parents feed their young for a period of 11-12 days.

Banded Blue-black Grosbeak male carrying seeds to two growing nestlings.

These birds are quite shy, and I hadn’t seen them on my own property, Finca Cantaros, until the last week of August. At dawn on the 23rd, armed with my newfound acquaintance with the species, I found a pair in the early morning fog; both were carrying nesting material.

Our property lies at 1187 m above sea level; 1200 m is reported to be the high point of their range. Fortunately, the reclusive Blue-black Grosbeaks have a healthy population and are not globally threatened. Their range is from Southeastern Mexico to Bolivia and Amazonian Brazil.

The nest was located in the tree to the right, just two feet above ground and carefully placed under sheltering leaves of Columnea polyantha, a Gesneriad I discussed in a recent post.

Having observed these hardy birds with their impressive bills, gathering food and feeding their young, I now feel a real fondness for them. Until Alison took me to see the nest, staying a respectful distance from it with the hope of seeing the adults, I didn’t even know of the existence of Blue-black Grosbeaks in my neighborhood. This is just another example of the importance of familiarizing people with the natural world. It’s really only when I’ve learned about the daily life of a bird or a mammal or even a plant–and become aware of its challenges to survive, its friends and its enemies–that I begin to care about it in an active way. Maybe this is because our conscious minds allow new knowledge and new friends to settle into new territory of our brains. We become vigilant on their behalf. It is an almost autonomous process I have come to love.

Silhouette of female Blue-black Grosbeak with nesting material in early morning light and fog at Finca Cantaros, August 23, 2016

Notes & References

* Cyanocompsa cyanoides, named in 1847 by Baron Nöel Frédéric Armand André de Lafresnaye, a French ornithologist and collector. In 1914 Baron Lafresnaye’s collection of over 8000 bird skins became part of the Louis Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology, a natural history research museum at Harvard University.

Handbook of the Birds of the World, digital edition.

A Guide to the Birds of Panama by Robert S. Ridgely and John A. Gwynne, Jr.

Wikipidia re Monsieur Lafresnaye.

Male Blue-black Grosbeak seen with nesting material on August 23, 2016 at Finca Cantaros, 6:00 AM

To email me about this post, please click here.

- September 2, 2016

- fauna

- Comments closed

Children in My Path–People II

Children at the school playground in Mashpi, Ecuador, 2014

In my last post I departed from nature and presented adults I’ve encountered over the past four-plus decades. Today: little people.

The secret to photographing children and young people is that there is no secret. Capturing their special essence takes trust, split-second timing, and limited expectations. In short, it seems like a felicitous accident if the image looks reasonably spontaneous and without frozen smiles. Getting a group of children together for a photo must happen quickly, before they have time to think about it. For the Ecuadorean kids above, though they were curious about me and drew together to make a tourist happy, I can see after the fact that some were not perfectly comfortable granting the request. But look how they bonded together–seven of the ten put their arms around or otherwise embraced each other, as if to reassure themselves there was no danger from this stranger or her camera.

Boy with distinct eyebrows, clutching roses, Mashpi, Ecuador, 2014

I usually ask permission to take a person’s photograph, though that can lead to abject failure. But on occasion I am able to capture a certain authentic spirit and mood that the children are feeling, and what I happen to be doing with my camera has little influence on their expressions, vitality or body language. Those pictures, taken without instructions except perhaps where to stand for a preferred background, reflect the inner instinct and energy of the child and usually turn out best. Asking for a “say cheese” is asking for a forced face–the essence of the moment evaporates. In my experience, going through the motions begging for a smile yields forgettable results.

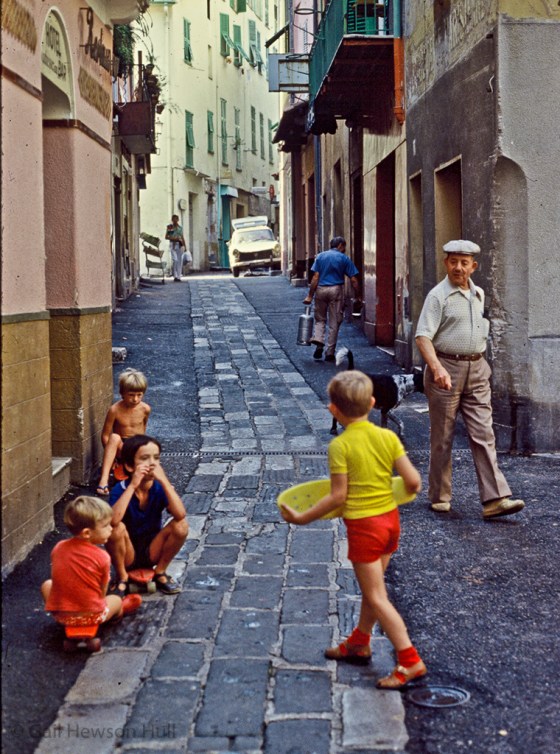

I’ve taken other photographs without express permission or even the awareness of the subjects, and these capture children just being themselves. An image’s success is due primarily to fortuitous timing (happy chance/sheer luck). Only the photos of the boy on the Lincoln statue below and the children on a street in Villefranche fall fully into this category.

Not having had children of my own, I cherished time spent years ago playing with my siblings’ children, and in later years in Costa Rica, listening to our property caretakers’ children at play, or watching them quietly drawing or inventing their games. Since my time with young children has been quite limited, I have never been gifted at communicating with them. Perhaps the effort to capture a child’s image in a photograph reveals an unacknowledged wish to make that child mine, to get close, if just for a moment! Or maybe it’s just the sudden inspiration of lovely lighting and the magic moment itself. I value that child’s time and willingness to be a subject. Being able to show the photo on the camera’s screen to the curious child afterward gives me pleasure and a sense of reciprocity, especially when that revelation seems respectful and true.

Songs of Innocence, by William Blake (1757-1827)

When the voice of children are heard on the green

And laughing is heard on the hill,

My heart is at rest within my breast

And everything else is still.

{Nurse’s Song, st. 1}

Brother and sister, Zailyn and Jefferson, San Vito, Costa Rica, 2015

Boy watching Harvest Day Parade from the statue of Abraham Lincoln, north side of San Francisco City Hall, California, 1978 (digitized from aged slide). My first photo of this subject was a profile, with the boy on his feet, elbow resting on Lincoln’s head, watching the parade passing by on the street below. Then he started to slide down, and looked up at the precise instant I snapped a second shot.

Skateboarders, Villefranche, France, 1982 (digitized from aged slide)

Keiner with new dog, San Vito, Costa Rica, 2010

Leo, with squirt gun, Rio Negro de San Vito, Costa Rica, 2010

Ngöbe Buglé girl, La Casona, Costa Rica, 1990 (digitized from aged slide)

Girl on her First Communion day, Tortuguero, Costa Rica, 2012

Holiday outing, Finca Cantaros, Linda Vista de San Vito, Costa Rica, 2014

Girls on the beach at Tortuguero, Costa Rica, 2012

Lilli, Linda Vista de San Vito, Costa Rica, 2008

To email me about this post, please click here.

- July 28, 2016

- people

- Comments closed

-

Recent Posts

- Movers & shakers and kleptoparasites September 5, 2021

- Birds That Cheered Me in 2020 January 2, 2021

- Solitude for Art and Birding September 25, 2020

- PHOTOGRAPHY BEARING WITNESS May 4, 2020

- DESERT BIRDS OF ARIZONA March 26, 2020

- BOSQUE DEL APACHE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE January 10, 2020

- Santa Fe Trails September 28, 2019

- A Hybrid Bird at Finca Cántaros January 17, 2019

- Birding at Caño Negro National Wildlife Refuge September 17, 2018

- Remembering the Bush Dogs June 8, 2018

Archives by month

Click the icon below to visit Finca Cantaros on Facebook:

Search Foto Diarist

Search Post Categories

-

Join 111 other subscribers

RSS Links

Blogs I Follow