Two Costa Rican Cuckoos

Squirrel Cuckoo, Finca Cantaros, Linda Vista de San Vito

Throughout the Old World and the Americas there are 127 species of cuckoos inhabiting both temperate and tropical regions. One can see twelve species (including three Ani) of these slender long-tailed birds of the Cuculidae family in tiny Costa Rica–nine residents and three migrant species. They frequent habitat from sea level, including the endemic Cocos Cuckoo on Cocos Island, 342 mi (550 k) from Costa Rica’s Pacific shore, and then up to 7,500 ft (2,300 m) elevation. At least two of the higher elevation species may be seen in our county of Coto Brus, and one quite regularly—the Squirrel Cuckoo–in my own backyard.

Squirrel Cuckoo, Finca Cantaros

Why do I like the word “cuckoo”? Does it remind me of the slang word for “crazy” that I applied to my brother and sister when we were children, usually accompanied by a twirling finger pointed at the side of my head? (Do kids still do that?) Or does it remind me of the charming German clocks of yesteryear, whose fame depended upon a carved wooden bird emerging on the hour from behind closed doors to sing “coo coo”? And why was the Common Cuckoo of Europe selected to represent time marching forward? Why not the rooster?

It seems the Common Cuckoo’s song was traditionally viewed throughout the continent as the first joyful sign of spring, of rebirth, of nature primed for mating. Recognizing the power of this popular, hopeful symbol of the end of winter, 17th century clockmakers in the Black Forest village of Schönwald invented the Cuckoo Clock and crafted new iterations over centuries. For those with a bent for this sort of thing, there are some very cool contemporary Cuckoo Clocks.

Squirrel Cuckoo, Finca Cantaros

Returning to my property in Costa Rica, the Squirrel Cuckoo usually announces it’s in the vicinity with a startling, loud whistle (KIP-weyeeeeeu) reminiscent of a construction worker’s response to an attractive lady passing by. In breeding season, the Squirrel Cuckoo is quite apt to produce a long series of whip or pwit sounds, with a prolonged churrrr when the object of attraction draws near.

Squirrel Cuckoo, Finca Cantaros

Though not as multicolored as some other tropical birds, the Squirrel Cuckoo’s upper plumage epitomizes the bright color “rufous”. A rather large bird with distinctive habits, it is relatively common and hard to miss or misidentify. Once spotted at close range, the Squirrel Cuckoo doesn’t immediately fly away, but tries to hide behind arboreal vegetation, continuing to hunt in a squirrel-like manner, hopping from limb to limb in search of insects, especially its favorite food, caterpillars. Often described in bird guides as “furtive” or “skulking”, the Squirrel Cuckoo has an unnerving way of peering through leaves and turning its head sideways to look down, its red iris beading in on the intruder.

On a recent San Vito Bird Club trip to Cuenca de Oro, a property a few hundred feet below our elevation at Finca Cantaros, our president, Alison Olivieri sudden stopped short and looking up through her binoculars said, “Look where I’m looking—right overhead—I don’t want to take my eyes off this bird—the Black-billed Cuckoo!”

Black-billed Cuckoo, Cuenca de Oro, San Vito de Coto Brus

She was very excited, a common feeling among birders when something rare comes along. Fall passage migrants of the Black-billed Cuckoo are called “very rare at best” on the Pacific slope. Because these migrants are silent as they pass through Costa Rica on their way to wintering grounds in South America, it was all the more remarkable that Alison spotted it. And the rest of us soon shared the excitement, as we enjoyed watching the Black-billed Cuckoo scanning the surrounding branches and bushes for caterpillars or katydids, until it finally gave up and flew away.

May we remember again the Common Cuckoo of Europe, who inspired even Shakespeare: here are his lines in recognition of this fertility symbol in Love’s Labor’s Lost (V, ii, 902)

When daisies pied and violets blue,

Red-Tailed Squirrel, Finca Cantaros

And lady-smocks all silver-white,

And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then, on every tree,

Mocks married men; for this sings he,

Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo: O word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear.

*******************************************************

References:

Smithsonian.com The Past, Present and Future of the Cuckoo Clock, by Jimmy Stamp, May 17, 2013.

The Birds of Costa Rica, A Field Guide, by Richard Garrigues and Robert Dean, copyright 2014, published by Cornell University Press, pp. 174-176, and p. 370.

A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica, by F. Gary Stiles and Alexander F. Skutch, copyright 1989 by Cornell University, Cornell University Press, pp. 183-188.

- December 2, 2015

- fauna

- Comments closed

For France

The photographs are of landscapes and birds in beautiful Scotland where I traveled in July of this year with my husband, Harry.

May they bring to you a semblance of peace and continuity.

Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve, Wester Ross

The view from the West Mainland of Orkney near Scara Brae, a neolithic village where most monuments date between 4000 and 5000 years.

River descending to the sea in Wester Ross.

Isolated farm on highland loch.

Nature reserve on West Mainland, Orkney.

Grey Heron and Oystercatcher, Mull

Ancient ruin on the Isle of Iona, just across from Mull.

Isolated farm on loch near Ullapool.

Thrush under black current bush, Inverewe Garden. Note black current in right corner, about to be eaten.

Iona Abbey on the Isle of Iona, just off the Isle of Mull. Its origins trace to St. Columba and go back to the sixth century when it was the foundation of a monastic community and nunnery. Attacked by Vikings who massacred everyone in 806; it was rebuilt and expanded various times after attacks. Iona Abbey is home today to an ecumenical Christian religious order, and remains a popular site of Christian pilgrimage.

- November 14, 2015

- fauna, landscape

- Comments closed

The Persistence of Turtles

White-lipped Mud Turtle (Kinosternon leucostomum) at Finca Cantaros in a fruit orchard. Found in Pacific slopes from Costa Rica to Ecuador; Caribbean slopes from Mexico to northern Colombia. Females lay 1-4 eggs on the ground under leaf litter between July and October.

Turtles may be one of the first animals to capture a child’s imagination. To see the final drawing of Aesop’s winning tale of The Tortoise and the Hare, and to learn that “slow and steady wins the race” is to empower a child to keep trying and never, ever, give up. For adults, the fable’s lesson has been retooled by corporate motivators to inspire hard work and profit-making. Turtles have colonized most biomes on earth except Antarctica, so people everywhere are exposed to them and seem to develop affection for them precisely because, unlike other reptiles that can move or strike in the blink of an eye, most turtles are tranquil and non-aggressive. They can be trusted. My mother, not exactly an intrepid outdoorswoman, nonetheless felt protective of turtles, stopping to pick up small cooters, box or pond turtles on busy roads in our Massachusetts neighborhood to remove them from harm’s way.

The plastron (underside) of the White-lipped Mud Turtle has a hinge, and the animal can completely withdraw into its shell, sealing the opening by closing the plastron against the carapace.

Turtles persist. They age, but hardly grow old! Their organs don’t deteriorate with time as mammals’ do. Herpetologists at the American Museum of Natural History have learned that the liver, lungs and kidneys of a 100-year old turtle are almost indistinguishable from those of a juvenile counterpart, inspiring research of the turtle genome for novel longevity genes. Some Seychelles and Galapagos tortoises have lived to 175 years before dying of old age—perhaps as many as 250 years, as claimed for Adwaita, a giant tortoise that died in a Calcutta zoo in 2006.

And at the Smithsonian Institution, herpetologists found turtles’ hearts are not stimulated by nerves, and don’t need to beat constantly. Having the power to turn off their ticker at will may account in part for their longevity. The herpetologists’ research also found that among some populations of sea turtles, females don’t reach sexual maturity until they reach 40 or 50 years of age, and that could be “a record in the animal kingdom.” Then they continue producing eggs until they die.

Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentine) at Finca Cantaros, sunning on a log at the edge of Laguna Zoncho. The female lays up to 80 eggs.

At Finca Cantaros, with its year-round pond and rainy season marsh conditions, turtles seem to thrive. We find them as half buried eggs, sunning on logs, lumbering along on forest trails, swimming with their noses aloft in the pond, and even roaming grassy fields under fruit trees. The main predators here, especially of turtle eggs, must be animals such as the rather common opossum (“zorro”), armadillo, tayra, a weasel-like animal (“tolomuco”), and the odd otter (“nutria”). In turn, turtles are omnivorous, consuming plants, fruits, insects, mollusks, frogs, and fish.

Red-footed Tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonaria) removed from danger on a dirt road in the Pantanal region of Brazil. Vulnerable to extinction due to over-collection for food and the pet trade, its main threats are jaguars and humans.It can reach 16 inches in length. Tortoises have completely terrestrial habits and this tortoise lives about fifty years.

Reminding me of the divine freedom I enjoyed as a young New Englander to wander woods and meadows and explore brooks, marshes and ponds, every time I find a turtle even now I feel pure exuberance. As a child I tried to imagine what it would be like to be them: swimming so encumbered; chomping on watercress, minnows and crayfish; hiding in dappled waters. Perhaps it is their benign nature that appeals, their unique architecture, and their impenetrable eyes glinting from ancient lineages going back 230 million years or more. From childhood wading, when I just wanted to catch and hold a turtle to study its shell and wait for its head to emerge from the carapace, I have since been convinced that turtles deserve not just wonder and respect, but active protection. About half of the world’s only 250 species of turtles today are considered endangered or threatened.

Red-footed Tortoises may aestivate (go into a dormant or torpid condition) in dry weather for several months. The scales on their shells are called skutes.

When I think of the “progress” that co-opted some of the beautiful turtle and frog territories I explored as a child and teenager, multiplied everywhere and unceasingly worldwide, my inherent optimism tends toward despair. Turtles have been hardy and critical survivors, contributors to the health of diverse fresh and salt water ecosystems, even deserts, but they are poorly equipped to deal with the myriad and expanding human threats from habitat loss to climate change. Threats to sea turtles seem particularly acute.

Evolutionary biologists seem to agree that somewhere in our distant past we humans share an ancestor with turtles. We can thank that ancestor for what some neuroscientists call our reptilian brain, the primitive, instinctive part of the brain that governs the functions over which we have no or little conscious control, like balance, breathing, heart rate, and body temperature. We must hope that the human brain’s more complex limbic system and neocortex, which contribute to making us the rational, caring and creative innovators we are capable of being, will soon, with farsighted leadership, enable earthlings to properly prioritize and insist on sustainability for all precious life.

A recently hatched unidentified turtle (2 inches) found at the highest point of the Finca Cantaros property. Turtles are on their own from the moment the egg is laid. They remain solitary throughout their lives except at mating time when males must actively court females in order to be selected.

Sometimes I feel that I live in a bubble in Costa Rica, surrounded by lush vegetation in my seven hectares, in a country that protects a larger percentage of its natural resources than any other. I have created a nature reserve, and am “acting locally” in what I think is a responsible way. But how do I quash the guilty sense that I should be doing so much more to help turtles and other creatures everywhere?

****************************************************************************************

References:

Slow is Beautiful, by Natalie Angier, in Science Times, New York Times, December 12, 2006. Many of the facts in my post were selected from Ms. Angier’s comprehensive article, highly recommended for those interested in turtle biology and conservation.

A Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica, by Twan Leenders. A Zona Tropical Publication, 2001

Amphibians and Reptiles of La Selva, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean Slope–A Comprehensive Guide by Craig Guyer and Maureen A. Donnelly. University of California Press, 2005.

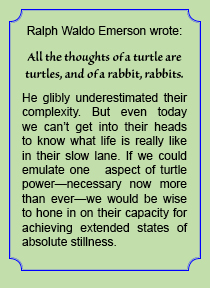

The Natural History of Intellect by Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1893: (From Bartlett’s Quotations.)

Recommendation:

Self-Portrait with Turtles, A Memoir by David M. Carroll, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004.

I loved this book. David Carroll is a New Hampshire illustrator, author, naturalist and conservationist whose life’s work has centered on turtles and the natural systems in which they live. He was selected as a MacArthur Foundation Fellow in 2006.

- November 12, 2015

- fauna

- Comments closed

-

Recent Posts

- Movers & shakers and kleptoparasites September 5, 2021

- Birds That Cheered Me in 2020 January 2, 2021

- Solitude for Art and Birding September 25, 2020

- PHOTOGRAPHY BEARING WITNESS May 4, 2020

- DESERT BIRDS OF ARIZONA March 26, 2020

- BOSQUE DEL APACHE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE January 10, 2020

- Santa Fe Trails September 28, 2019

- A Hybrid Bird at Finca Cántaros January 17, 2019

- Birding at Caño Negro National Wildlife Refuge September 17, 2018

- Remembering the Bush Dogs June 8, 2018

Archives by month

Click the icon below to visit Finca Cantaros on Facebook:

Search Foto Diarist

Search Post Categories

-

Join 111 other subscribers

RSS Links

Blogs I Follow